Hi! It’s taken awhile, but I think I’ve figured out a format I like for this newsletter. I hope you do too.

There are three sections:

Things I wrote. Expect these to be somewhat off-the-wall 3/4ths baked ideas about cities, technology and other things that structure the world we live in. I don’t expect to be right about all of these, but do intend to commit to an idea strongly enough to learn where I’m wrong, and show my thinking a bit. I nominate you as my editor :)

Best Of. Short lists of links to what I’ve been reading, writing, thinking, watching and listening to. Consider this a summary of what’s stuck with me the most over a longer unit of time than other mediums are built for.

One simple thing you should do. One thing where I’ve thought, “This is amazing, everyone should try this!”

I’ll aim to send this about every 1-3 months.

I’d love your feedback, online or offline. brendanib@gmail.com, 510.289.7784, or @irvinebroque

Deliveries in the Hood

There’s evidence that Amazon optimizes for serving higher-income neighborhoods, because that’s where high value customers are.

After some pressure, they’ve started offering the same level of service in some lower-income neighborhoods, and have been providing a 50% discount on Amazon Prime to welfare recipients. This makes Amazon appear available to everyone, but it’s actually an equality policy that masks an inequity - how do the packages arrive safely?

You probably work at an office, so even if you live in San Francisco, the package theft capital of California, you can have packages delivered there. Most people don’t work in offices though. Without an office, where do you have things delivered if you live in a place where packages can’t be safely left on your doorstep?

Lockers! Said Amazon in 2011 to skeptical New York bodega aficionados, San Francisco residents, and Seattle early adopters.

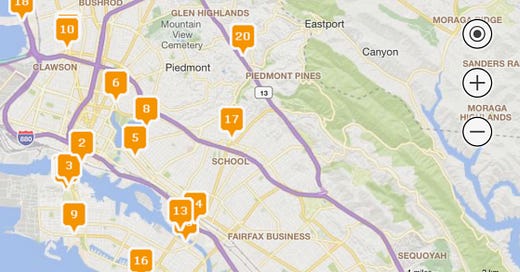

Check out this 2019 map of lockers though:

No lockers in the core of East and West Oakland. And if there’s no locker near you, you might as well go to a physical store.

I don’t have research to back this up, but having done almost all my shopping online for the past 8 years (except Berkeley Bowl!) I think this is a large inequity that deserves research and coverage.

Shopping at a physical store for essential goods consumes bandwidth:

How will I get there? (I don’t have a car and AC Transit is hella late)

When will I have time to go? (My job has no chill about flexible hours and breaks)

Should I go to somewhere in my neighborhood with higher prices, or make the trek to Target or Walmart?

Conversely, buying things online requires:

A phone

A debit or credit card

1-2 minutes of time

No transportation, no logistics planning

Price comparison takes 1-2 30 second searches

I’m convinced that having to go to a physical store imposes a bandwidth tax that online shoppers do not pay

This inequity has been in effect for about 5 years for household goods. But an interesting thing is starting to happen with grocery delivery services, like Amazon Fresh, Instacart, Good Eggs, Farmstead - you choose a delivery time:

UPS might leave a package on your doorstep at 1pm when you’re not home. But with grocery delivery, you can choose to have groceries delivered only when you’re home. A solution to milk going sour on your doorstep in the sun can actually put people on a level playing field.

Similarly, Amazon recently rolled out the option to choose a weekly delivery day, in an effort to reduce its carbon footprint. As a side effect, if you live in a place where packages get stolen, you can choose a delivery day when you’ll be home (though you can’t yet choose the time of day).

All of this brings me to Community Foods Market, a grocery store in West Oakland that opened fairly recently. West Oakland is a notorious food desert - it hasn’t had a real grocery store for 40 years.

Opening the store was expensive and hard. Brahm Ahmadi started working on it in 2010, spent years raising money from local investors, and building the store required a $3,000,000 construction loan - my guess is the total cost of opening was well over 5 million.

Opening the store is a monumental achievement. I hope it works. I love grocery stores. Berkeley Bowl is basically my second home. But so much has changed since 2010, that I’ve been thinking a lot about whether a physical store would be the most effective approach in 2019, if physical stores impose a bandwidth tax that (wealthier) online shoppers do not pay.

For example, $1m would pay for ~5000 annual Amazon Fresh subscriptions. Negotiate with Amazon and you could likely double or triple that number. Or you could start your own local delivery service. West Oakland has about 40,000 residents. I’m sure there are tons of structural barriers to overcome, like helping some older residents move from cash to paying online, but it seems worth considering - is our nostalgic attachment to grocery stores getting in the way of having maximum impact or building more sustainable businesses? I’d love to see more radical experiments for solving food deserts - particularly experiments that enable the same level of convenience that other neighborhoods benefit from. Otherwise, I think we’re headed towards separate systems for rich and poor. That tends not to end well!

Open-source short positions (software eats activist investors)

What if instead of charging for your product, you made it free, and profited by shorting competitors?

Take Zoom. Great SaaS company, terrible software. Videoconferencing should be based on open protocols. It shouldn’t take a giant enterprise software company for peer-to-peer video to work, even if NAT traversal is hard. If you’ve played with WebRTC, you know that we’re not that far off from video chat working natively in a browser with only a few lines of code. /end programmer rant

I’d argue (knowing this is a hot take!) that Zoom is really just rent seeking on the knowledge economy, to the tune of a 30b valuation. We don’t have open and widely shared standards and protocols for video conferencing (like we do for email or websites), so Zoom gets to profit off of this gap and charge all of our companies money, just to get something so basic that it was in 90s movies to work.

But how would you compete with Zoom?

It’d be foolish to start a “better Zoom” SaaS company, and just charge less money. Acquiring customers is expensive, hard, and Zoom already captured the low-hanging fruit of customers stuck on even more ancient software. Don’t you know everything goes in cycles?

What if you built a free piece of software, built on open protocols, that did everything Zoom did, better, for free, and you were confident that 10% of Zoom’s existing customers would switch? Assuming you could time it right, you could take out a short position on Zoom and make quite a lot of money.

Most importantly, you’d avoid the work and complexity of making money - pricing, sales, etc, which tends to be at least 50% of revenue for SaaS companies.

This is, like, how activist investors’ short positions work! You do a bunch of research, and try to convince people that you’re right, and the company is nonsense. Then it goes on and on and someone makes a documentary about you and you lose a lot of money, even though you’re right. Well, sometimes.

Activist investors only have two tools - heaps of money and PR. They try to convince other investors, but don’t really have tools to convince a company’s customers or users. If I come out with a short position and denounce Overstock.com for accounting fraud, Overstock’s customers are like, “Cool but will my couch be delivered by Saturday?” They’re not aware of and do not care about the antics of Patrick Byrne.

Free or open/distributed software could change this. I don’t care if the company I’m buying from is overvalued, but wait you said I can get this for free or 10% of what I’m paying today? You have my attention.

I write this because, in a weird way, this is exactly what many people are trying to do with Bitcoin and blockchains. Before you cover your ears, roll your eyes and close this tab, follow me for a minute.

If you believe that the purpose of the internet is to break down barriers (a somewhat unpopular view in today’s Silicon Valley, where most people treat the internet as a vehicle to for wealth creation and value capture), it follows that you want to drive down the cost of software to as close to zero as possible. This is what Facebook is trying to do, even if you don’t believe me because they do so with ads and were forced by crises to build walled gardens rather than the open platforms they dreamed of in the early years.

There are tons of ways to make something cheaper, but I only know of two models for driving the price barriers of software down to zero:

Model 1: Give the product away, and charge for something else. Examples include Facebook (free product for consumers, charge companies for ads) and enterprise open-source (software is free, support and services are expensive).

Model 2: Propose new interoperable standard and convince powerful companies to adopt it. Examples include TC39 (If I want to change how Javascript works, I propose the change to the TC39, the standards committee) and OpenSSL (which made the web safer (until it didn’t!) by getting nearly everything to use it)

In Model 1, you can make a lot of money and have people hate you for making the world better. In Model 2, you can make no money and have nerds yell at you for making the world better. It’s really quite sustainable and fun!

Indirectly, each of these models might attack the value of established, rent seeking companies. Linux is free, and increased adoption hurt Microsoft’s server business. The web gets better through improved standards, and big companies have less leverage over closed ecosystems. But they’re not direct attacks on incumbents.

Model 3 is crypto. There’s a ton of smoke and mirrors and people yelling blockchain blockchain blockchain, and libertarian thinking that I don’t roll with, and you probably don’t either, which is why the connection isn’t intuitive. But:

Bitcoin is effectively a short position against fiat currency and the financial system. By holding Bitcoin you’re saying, “I don’t believe the existing system will succeed in the future”.

People work on Bitcoin and other crypto stuff for free

The people who do this tend to believe in breaking down barriers and transaction costs

When you add this, up, the collective set of people invested in Bitcoin act as one giant activist investor with a short position against government-issued money. Except unlike an activist investor, they have software with real users, rather than graphs and charts and CNBC appearances.

Similar to how Ethereum and other platforms are trying to extend the Bitcoin model to more use cases, you can apply the same logic about short positions to the use cases these projects are entering. Someone building a decentralized platform for freelancers is effectively shorting Fiverr, Upwork, and all the centralized marketplaces that profit from connecting people with work.

Most (all?) of these types of projects haven’t taken off yet. One argument is that it’s early. Another is that crypto is hard to use. Both are probably true. But I’d argue that people working on these things would be smart to figure out structural ways to earn a one-time profit from the act of driving down the cost of software or marketplaces to near-zero. And maybe call Bill Ackman.

An incomplete list of unsolved flaws with this idea:

It only works when the company you’re shorting has a single line of business or product. Most publicly traded companies have many products, making it harder to short them based on only a single one.

Many companies aren’t public, and can’t be shorted.

Timing is incredibly hard, and short options expire within 1-2 years. To me this is the hardest part, and the thing that prevents me from putting more chips on the table when buying put options on things like oil companies. They’ll die eventually, but it’s hard to say when, even if you’re the direct competitor.

Books:

Range by David Epstein. Reinforced my pride in being a generalist.

Sixth Man by Andre Iguodala. Smartest player in the NBA.

Scarcity by Sendhil Mullainathan. The “bandwidth tax” is my favorite new lens to view human behavior.

Podcasts:

Raj Chetty finds that helping poor people navigate the world of rich people has dramatic positive impacts on children. People and community can be more powerful than financial incentives.

The worst NBA owner was even worse than you imagined, and Ramona Shelburne is better at podcasts than I imagined.

Nobody could make a podcast about referees as interesting as Michael Lewis does.

Movies & TV:

Music

Elsewhere:

“The feeling of scarcity is distinct from its physical reality.”

Risk capacity drives wealth (and without a safety net, inequality).

Aggregators won in the 2010s, but platforms are rising in commerce, content, and elsewhere.

A new fundraising strategy: lose as much money as you can, and then come back for more.

A high Tobin’s Q no longer spawns new competitors, indicating that returns to scale are increasing and enabling rent seeking.

Weak technologies are tempting. I’m looking at you, New York and LA.

More reasons why AAU is terrible: 12 year-old kids are tearing their ACLs. The NCAA may be worse for different reasons though.

A partial repeal of Prop 13 will make the 2020 statewide ballot, but does it need to hide as the Schools and Communities First Act? Taxing big companies is so popular that it might make sense to be more blunt.

Convertible bonds are really call options on risky startup stock.

Universal basic income (or full employment) may help wages accurately reflect social value.

The best defensive player according to DRAYMOND is Draymond.

One simple thing you should do:

Opt-in to 100% renewable power. Takes 10 minutes. Costs maybe $10 more per month for a typical household. Do it:

East Bay Community Energy (East Bay)

CleanPowerSF (SF)

PG&E Solar Choice (Statewide)

If you’re outside of California, and this isn’t an option for you yet, call your local representative and insist that it exist!